The Latin word nefas is a combination of the word ne, meaning “not,” and the word fas, which transliterates as “right,” but that’s not exactly right. It was more than that, something closer to the Chinese Dao, although the Romans were not Daoists by any means. Fas is the divine order of things, precariously balanced and beyond our rational comprehension.

According to the modern mechanistic view, the universe is reducible and understandable and we humans (as far as we know) are the most advanced thing in it. This accords well with the prior Judeo-Christian view, which spawned the current scientistic one, that said God put us in charge of everything, because we’re just that awesome.

Not so for the Romans. In some sense, they lived in a far richer world, a noumenal world chock full of magic and mysteries and spirits, large and small. There was a god for everything, including separate ones for the door frame, the lock, and the hinges.

Amid such a maelstrom, the Romans needed a way to make sense of it all, and as you might expect, augury was big. It was common for Romans of high and low class to seek a reading—animal entrails were popular, although oracles were better if you lived close enough to visit one—prior to any travel or large purchase.

Fas was the way all this fit together. It was the book the augers read. And since, in the Roman view, mankind was not the king of the mountain, the Romans did not expect that this divine puzzle would be all good, free from pain, or the best of all possible worlds. In fact, they often expected the opposite, which is why they sought augury in the first place.

Thus ne + fas is more than simply “not right.” It’s against the prescribed natural order. We might call it sin, but thanks to our Victorian forebears, that word has a strong sexual connotation, which would’ve been largely absent for the Romans, who might have graphical depictions of sex acts—fertility art—in their living rooms.

If pursued intentionally, anything nefas was an abomination, something you would expect to draw the anger of the gods. Romans would have witnessed a nefas act the same way school children might witness willful misbehavior on the playground, or the way adults witness a car wreck, with an uncanny mix of horror and fascination.

But it needn’t be intentional. Nefas could also imply a kind of breakdown or kink in the world, and this was what the consuls would check for every morning before the meeting of the senate. If the entrails were “not right,” a consul—remember, there were always two, kind of like co-presidents—could declare a Nefas Day, a bad day on which to conduct state business, and so the senate would not meet.

As you can imagine, this power was regularly abused by political factions seeking to manipulate senatorial debates, and eventually the senate had to pass legislation limiting the number of Nefas Days a consul could declare. (In other words, the senate was telling the world and all the gods in it how often they were allowed to mess with things. Such are the dreams of regulation.)

I think “Nefas Days” are a great idea—not for Congress, perhaps, but for the rest of us. We all need one from time to time. I use them to help my weight loss. For me, a Nefas Day is one on which I'm allowed to eat whatever I want, which gives me the strength to stick with calorie restriction and exercise because I know a scheduled break is always coming.

The trick, as the Romans discovered, is regulating its abuse. There always needs to be a lot more right than not-right or things fall apart. But then, that's the trick to everything.

This past year, the mix has not been in my favor. This isn’t a grievance column, so suffice it to say things of late have been more not than right, and that is why this letter is so late.

There’s another entry in the Log of Strange Concordances, where I capture those aspects of the real world that bring us closer to the world of Science Crimes Division.

… When we humans do these things, we call it lobbying. Successful agents in this sphere pair precision message writing with smart targeting strategies. Right now, the only thing stopping a ChatGPT-equipped lobbyist from executing something resembling a rhetorical drone warfare campaign is a lack of precision targeting. AI could provide techniques for that as well.

A system that can understand political networks, if paired with the textual-generation capabilities of ChatGPT, could identify the member of Congress with the most leverage over a particular policy area—say, corporate taxation or military spending. Like human lobbyists, such a system could target undecided representatives sitting on committees controlling the policy of interest and then focus resources on members of the majority party when a bill moves toward a floor vote.

Once individuals and strategies are identified, an AI chatbot like ChatGPT could craft written messages to be used in letters, comments—anywhere text is useful. Human lobbyists could also target those individuals directly. It’s the combination that’s important: Editorial and social media comments only get you so far, and knowing which legislators to target isn’t itself enough.

This ability to understand and target actors within a network would create a tool for AI hacking, exploiting vulnerabilities in social, economic and political systems with incredible speed and scope. Legislative systems would be a particular target, because the motive for attacking policymaking systems is so strong, because the data for training such systems is so widely available and because the use of AI may be so hard to detect—particularly if it is being used strategically to guide human actors.

The data necessary to train such strategic targeting systems will only grow with time. Open societies generally make their democratic processes a matter of public record, and most legislators are eager—at least, performatively so—to accept and respond to messages that appear to be from their constituents.

Maybe an AI system could uncover which members of Congress have significant sway over leadership but still have low enough public profiles that there is only modest competition for their attention. It could then pinpoint the SuperPAC or public interest group with the greatest impact on that legislator’s public positions. Perhaps it could even calibrate the size of donation needed to influence that organization or direct targeted online advertisements carrying a strategic message to its members. For each policy end, the right audience; and for each audience, the right message at the right time.

Part of a short essay by Nathan Sanders, reproduced by Bruce Schneier on his blog, that does a good job of describing the immediate threat, which is probably why both of those guys have a much wider audience than I do.

In The Zero Signal I was looking even further. In the final chapter of the book, a genius chimpanzee described the next iteration of this mechanism, where AIs operating at the meta level search for indications of exactly the kinds of actions Nathan describes with the aim of inferring their owners' goals and strategies so that counter-strategies can be deployed by their own lower level AIs.

While that's the likely outcome, and also where democracy is headed this century, it might be a bit abstract for the casual reader. Or maybe I just don't pull it off well. Or both. You tell me.

Here is the essay:

https://www.schneier.com/blog/archives/2023/01/ai-and-political-lobbying.html

Here is the chapter:

I have not been following the news, but I have made it a point to follow the Twitter Files, if only because it is a fascinating study in information technology’s capacity for narrative warfare of the kind warned about in Science Crimes Division.

The establishment has always filled the news with propaganda. During the Vietnam War, Walter Kronkite lied to the American people every night—about the number of soldiers killed or how close the enemy was to their inevitable failure. The government has also often told us what we can or can’t see. Note they still haven’t released the Kennedy files.

But I don’t remember it ever being quite so overt and coordinated. We’ve long lamented the revolving door between defense contractors and the military, but the media and intelligence services have put the military-industrial complex to shame. I’ve never seen so many “former” spooks on TV telling me what to believe. If this many ex-KGB officers were TV analysts in Russia, we would cry havoc.

We can only assume that the mechanisms pointed at Twitter are also being pointed at Google, Facebook, YouTube, and elsewhere. There is certainly enough circumstantial and anecdotal evidence to suggest the existence of a large narrative coordination and control system. And it’s not in Russia. Or China.

I think some people shrug because they think they’re immune. But you’re not. Propaganda rarely convinces us that something we disbelieve is true. Not even you are so gullible. Rather, propaganda reinforces the prejudices and stereotypes we so desperately want—or fear—are true. The propagandist and his mark are codependents in an abusive marriage.

The otherwise good people who accept and perpetuate propaganda, like you, are not, for the most part, trying to be evil. Quite the opposite. Rather, they are in possession of a Noble Lie. That God hates gays. That MAGA is an existential threat (versus any other kind).

Truth is never so manifestly noble. Like light, it only ever comes in tiny packets like photons. We call them facts: a date, a quote, a Boolean condition. None of you would intentionally extinguish all the light in the universe, and yet, photons, like facts, are only ever experienced one at a time. None will ever outweigh the Noble Lie, and so one by one, they will all be got rid of.

All the easier when they turn dangerous. Facts, like photons, bounce about randomly in too great a number to be captured by anyone, and they often go where you don’t want or expect—and take people with them. It’s not only easier but better (the argument goes) to omit those that are potentially harmful, like the X-ray shield at the dentist, or to sprinkle a few extra on the other side of the scale, just to be sure someone doesn’t get the wrong impression.

The justification is simple enough to seem pure:

Propaganda is bad.

I am not bad.

Therefore, I am not perpetuating propaganda.

We only perceive the dangers immediately in front of us. When we throw democracy away, it will not be because we hate it but because we want to stop the other guys from having it.

Several of you checked in on me while I was AWOL. I see you and appreciate that. I had a request for old selections from social media. (Who has time for that anymore?!)

As Santa travels near the speed of light, time slows, which explains both how he is so long-lived and how his relatively small production team is able to make so many toys during the year.

But it does not explain how he is able to visit every house in one night. Bouncing a photon within and between every household in the world would still take a non-trivial amount of time. It would also be virtually impossible to remain undetected.

Rather, Santa makes only one light-speed trip on Christmas Eve, but that one trip is to every household simultaneously as a quantum superposition of all Santa-states, where he acts as a kind of carrier wave delivering presents that are already entangled with their owners—which is also how he can observe you remotely through the year.

That means every child MUST go to bed on Christmas Eve, and stay there. If Santa were ever observed, the wave function would collapse, and Christmas would be ruined for kids everywhere. You don't want that to be your fault, do you?

-me explaining to my future children why they need to go to sleep on Christmas Eve

There's a stock character in movies and television so common as to be trite: the over-sexed friend. They are typically supporting and rarely the star because their function is to serve as a warning to the main character that fucking for love is like bombing for peace. Even where this character is perpetually in a relationship, they are forever alone.

The earliest example I can recall off the top of my head is the character Violet from “It's a Wonderful Life.” Violet offers herself to George, but only superficially. As soon as he shares his hopes and dreams—anything other than his attention—she rejects him.

The over-sexed friend is often female, with Kim Cattrall's role in “Sex and the City” probably being the archetypal portrayal, but there are many male examples as well, such as Joey from “Friends” or Stiffler from the “American Pie” series (as well as all the knockoff roles that actor has played). Neil Patrick Harris has played a gay version a couple times.

I only mention it because I happened to catch part of a show my family was watching recently where the oversexed friend was yet another high school girl, and it occurs to me that despite a century or more of examples, we never get the lesson.

There is no greater sin than to break ranks in a time of peril. No transgression will get you excommunicated faster.

This is a real dilemma for soldiers who question orders or spies who reveal official secrets. (Would that they never needed to.) But there is no point—in a democracy, at least—where it should be bad form to question an orthodoxy.

But it is. And you all are the ones that enforce it.

It was impossible to question the existence of WMD in Iraq and still be called conservative. Your stance on issues that affected real people, from education to healthcare, didn't matter. If you didn't stand with the crowd and wave the yellow ribbon, you were a faggot commie liberal, and that's all there was to it.

A couple of years ago, if you questioned the Steele dossier or any of the absolute rubbish it created, you were a fascist. People called you that—and meant it.

It’s not the government doing this, or a bot farm in some foreign country. They may invent or amplify the threat. (Wartime powers dictate we must never feel safe.) But it’s always people like you that enforce the orthodoxy.

Common sense would dictate caution before excommunications and stonings. In the complexity of human relations, some slights are imagined.

But there is nothing common about sense. You are a large hairless ape, and you hoot with the best of them.

There are those authors, particularly in the indie space, who write thinly veiled political fables disguised as SFF or action/adventure novels. Besides that these tend to make very bad stories, they never work in their aim, which is to validate some world view.

The reason they don’t work is because, cognitively, human beings don’t relate to fiction as reality. They relate to it as if it were real, and in fact the very best books do exactly that: create worlds. But those worlds are distant. Human brains don’t perceive a relation between the seemingly real world of the book and the seemingly real world outside their window.

For one, fiction has a certain form, which we call genre, whereas life has no genre. This is why we say “truth is stranger than fiction” and are deeply dissatisfied by stories that rely on the kinds of unlikely coincidences that make up most of daily life.

Human beings can grow up on a steady diet of cyberpunk and still be shocked and angry when literally any of its horrors come true because the stories they read as adolescents don’t occupy the vulgar space of force and atoms. They occupy mythical space, transcendent space, and in fact, people often read specifically to escape vulgar space, which shows just how much they are not the same.

It’s not that we can't return from mythic space with applicable lessons. It’s that they’re always necessarily abstract. You can finish a work of literature convinced of the commonness of humanity, and five minutes later, complain about how some awful group of people on the news need to die. (If this were not so, humanity would’ve learned all the lessons it needed to centuries ago.)

The reason veiled political fables make for bad stories is much simpler. In a good story, all the choices the author makes serve it, which is why I am so adamantly opposed to “rules of writing” like “don't use passive voice” or “use adverbs sparingly.” It’s not that such things are wrong—although some are—as much as incidental or incomplete.

In art, there are no rules. But to the degree you are trying to write good fiction (and there are many, many kinds of writing besides fiction), then every choice you make—to use the passive voice or not, to open with the weather—should serve the story.

Spring writers, who are high on cleverness but low on experience, often try to break the rules seemingly for no other reason than to prove they can. Like a young adult discovering alcohol, there's an orgy of indulgence that usually results in regret.

The truth is, they reject “the rules” because they don't know how to follow them, which is to say they haven’t yet learned there are no rules but there are better and worse ways to tell a story. One of them is to make sure all your political devices serve it rather than the reverse. For one always suffers.

If you want to write a good political fable, then write a good political fable. Orwell did it with Animal Farm, which is not pretending to be science fiction. If you want people to pay you for your politics, be a journalist.

The world historian William McNeill argued that Homo sapiens had evolved specifically for synchronous ritual: dancing, chanting, marching in time. The anthropological data seem to support this. Researchers recently found that Sufis engaged in the dhikr, referred to as “the way of the heart,” will synchronize their heartbeats over hours of ritual. [1]

While this effect certainly relies on some real physical process like oscillator coupling, it doesn’t have a simple mechanical explanation. When sitting silently together mimicking each other’s behavior, lovers will also synchronize, where non-pair-bonded strangers will not.

(Interestingly, women’s heartbeats tend to attenuate more. In other words, in one experiment at least, women’s bodies settled closer to where their partners started and at a statistically significant rate. [2])

Scientists also observed this effect at a fire-walking ritual in Spain. Not only did participants’ and spectators’ heart rates approach synchrony, but "the degree of synchronicity was directly related to the level of social-emotional proximity. A fire-walker’s heart-rate patterns resembled those of his wife more than those of his friend, and those of his friend more than those of a stranger. In other words, the closer the social ties between two people, the more their heart rhythms were synchronised. This relation was so strong that we were able to predict people’s social distance simply by looking at the similarities between their heart-rate." [3]

There really is something deeply profound and necessary to belonging. It’s not a religious myth or political fabrication. Most people in post-industrial societies are missing it, and it’s leading us to ever-greater extremes of thought and behavior. To us, other people are at best inconveniences, at worst threats. We get on social media to post memes that admit as much. Like the toddler that wants you to hold her hand but also wants to walk down the stairs herself, we advertise our loneliness but never want to pay the price to cure it.

Of course, I'm hardly the first to make that observation, or this one: It’s not at all clear what we can do about it. We can’t blow up technology any more than I can pretend to believe in God. If I don’t actually love my wife, then I won’t experience the synchrony and all the attendant spiritual and physiological benefits.

I suspect this will be the major challenge for our species over the first half of the millennium: to replace what we lost without losing what we gained.

Immediately, of course, we need an exit from Perpetual War. Over the course of the century, we need an exit from fossil fuels and an antidote to narrative warfare. But all of that will be harder while we remain disconnected and suspicious of each other. Given that the only real threat to our continued existence is us, whether we survive will largely depend on whether and how we fill this gap.

[1] sapiens.org/biology/sufi-ritual-istanbul/

[2] sciencedaily.com/releases/2013/02/130213093220.htm

[3] aeon.co/essays/how-extreme-rituals-forge-intense-social-bonds

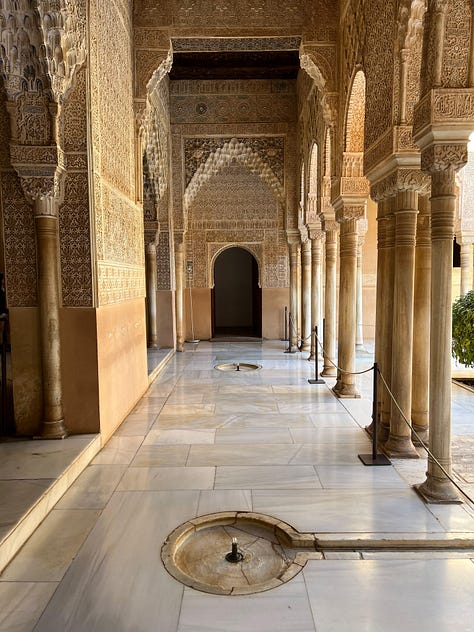

Here are some doors we encountered on our COVID-belated honeymoon last month.

Unlike the doors I used to share back in the day, these I actually captured myself. (What can I say? I’m a better poetaster than photographist.)

And here is this month’s picture of Henry. “What about me?”

That’s it for this time. I’m glad you’re here.