"On every new thing there lies already the shadow of annihilation. For the history of every individual, every social order, indeed of the whole world, does not describe an ever-widening, more and more wonderful arc, but rather follows a course which, once the meridian is reached, leads without fail into the dark. There is no antidote against the opium of time. The winter sun shows how soon the light fades from the ash, how soon night enfolds us. Hour upon hour is added to the sum. Time itself grows old. Pyramids, arches and obelisks are melting pillars of snow. Not even those who have found a place amidst the heavenly constellations have perpetuated their names: Nimrod is lost in Orion, and Osiris in the Dog Star. Indeed, old families last not three oaks. To set one's name to a work gives no one a title to be remembered, for who knows how many of the best of men have gone without a trace?"

—from "The Rings of Saturn" (1998) by W.G. Sebald

It’s not clear from the passage, but Sebald was paraphrasing a 1658 commentary on burial urns by physician and Renaissance man Thomas Browne. Actually, 'paraphrasing' might be generous. Unless one is familiar with the source material, it is impossible to know in The Rings of Saturn where it is Sebald and where it is the others he encounters, alive or dead, on his walking tour of the south English coast. But then that's part of his point: culture as ceaseless borrowing and re-inscription.

In other words, The Rings of Saturn turns plagiarism into art. The book is a kind of literary version of Warhol's “Campbell's Soup Cans.” At one point, Sebald spends the better part of three pages directly summarizing Borges' short story Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius. The report on Thomas Browne fills most of the first chapter.

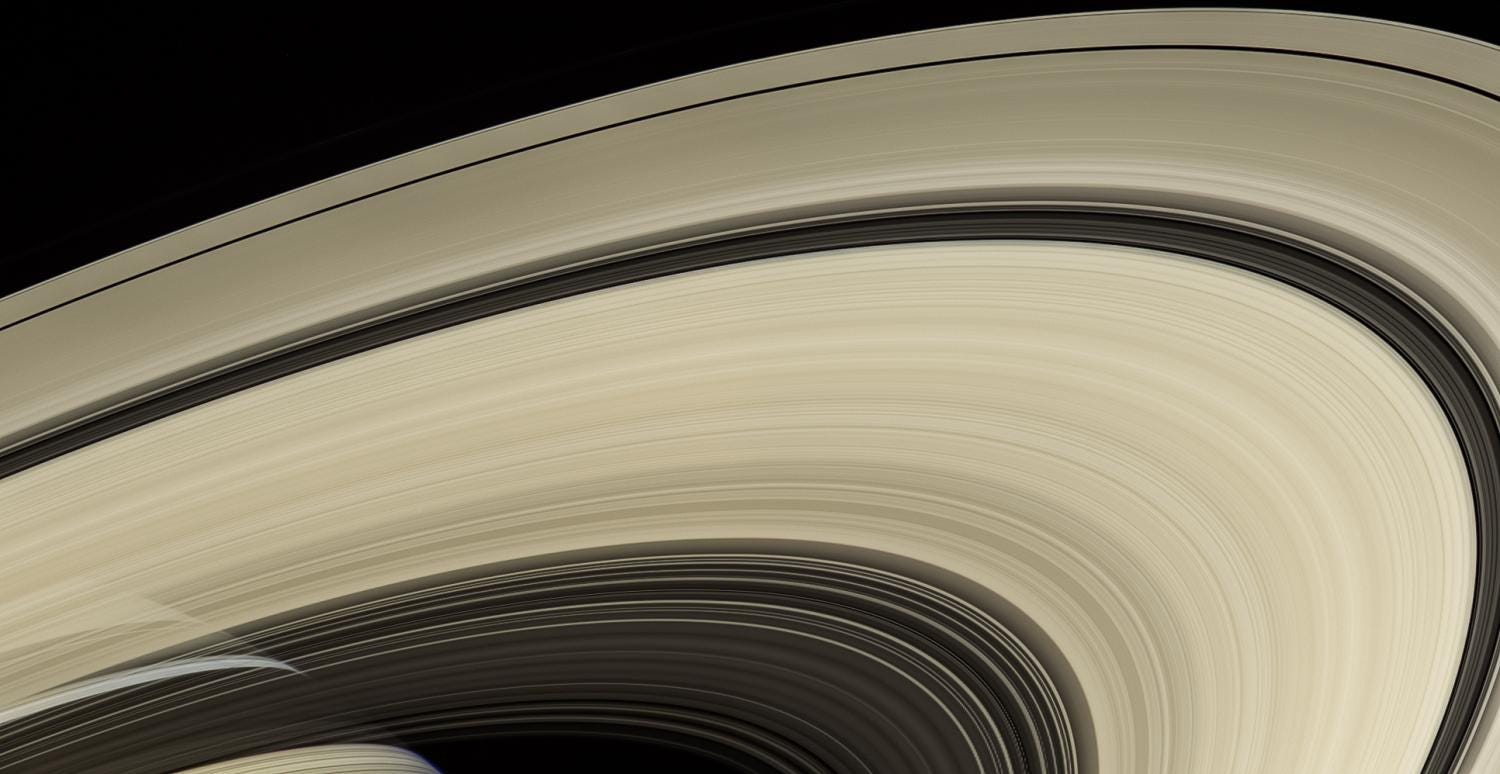

The meaning of the title, The Rings of Saturn, is hinted at in a quote from the Brockhaus Encyclopedia included in the frontispiece:

"The rings of Saturn consist of ice crystals and probably meteorite particles describing circular orbits around the planet's equator. In all likelihood, these are fragments of a former moon that was too close to the planet and was destroyed by its tidal effect."

The Rings of Saturn is a symbolic tour of the debris of Western culture, which its author found both grotesque and beautiful, more so that it was crumbling to sand, or so he argued in 1998 when the book was published. In Browne's phrase: arches and obelisks are melting pillars of snow.

Sebald writes (beautifully):

"As I strolled through Somerleyton Hall that August afternoon, amidst a throng of visitors who occasionally lingered here or there, I was variously reminded of a pawnbroker's or an auction hall. And yet it was the sheer number of things, possessions accumulated by generations and now waiting for the day when they would be sold off, that won me over to what was, ultimately, a collection of oddities. How uninviting Somerleyton must have been in the days of [its] industrial impresario, Morton Peto, MP, when everything, from the cellar to the attic, from the cutlery to the waterclosets, was brand new, matching in every detail, and in unremittingly good taste. And how fine a place the house seemed to me now that it was imperceptibly nearing the brink of dissolution and silent oblivion. However, on emerging into the open air again, I was saddened to see, in one of the otherwise deserted aviaries, a solitary Chinese quail, evidently in a state of dementia, running to and fro along the edge of the cage and shaking its head every time it was about to turn, as if it could not comprehend how it had got into this hopeless fix. The grounds, in contrast to the waning splendor of the house, were now at their evolutionary peak, a century after the heyday of Somerleyton. The flower beds might well have been better tended and more gloriously colorful, but today the trees planted by Morton Peto filled the air above the gardens, and several of the ancient cedars, which were there to be admired by visitors even then, now extended their branches over well-nigh a quarter of an acre, each an entire world unto itself."

In my youth, I thought—which is to say I wanted—Asimov to be right. I wanted history to be the result of impersonal material forces, physical or social, as distinct from, first, "heroic" histories, popular on the Right, which saw history as the gain of a few great-willed men moving chess pieces on a battlefield, and second, from Marxist theory, popular on the Left, which imbued history, a thing in itself, with a kind of manifest destiny.

Being a product of the Age of Discovery, Marx saw history like the course of a jungle river: existing separately from us, having a determined form that already extended to the future, inescapable. Society traverses this fixed river like a man in a canoe, bounded by its shores and destined to be carried across dangerous rapids to its terminus, which Marx described as a kind of economic utopia.

This vision of history, by the way, almost exactly matches "The Voyage of Life," a short series of paintings by Thomas Cole, which were produced in 1842, just two years before Marx met Engels. All three men, it seems, were products of their time.

Marx's vision is the opposite of Thomas Browne's. Where Browne saw life—the life of everything, from a person to history itself—as a parabola that, after reaching its zenith, descended in an arc to darkness, Marx saw it instead as an exponential progression, extending ever more rapidly to the heavens, like a chart of housing prices.

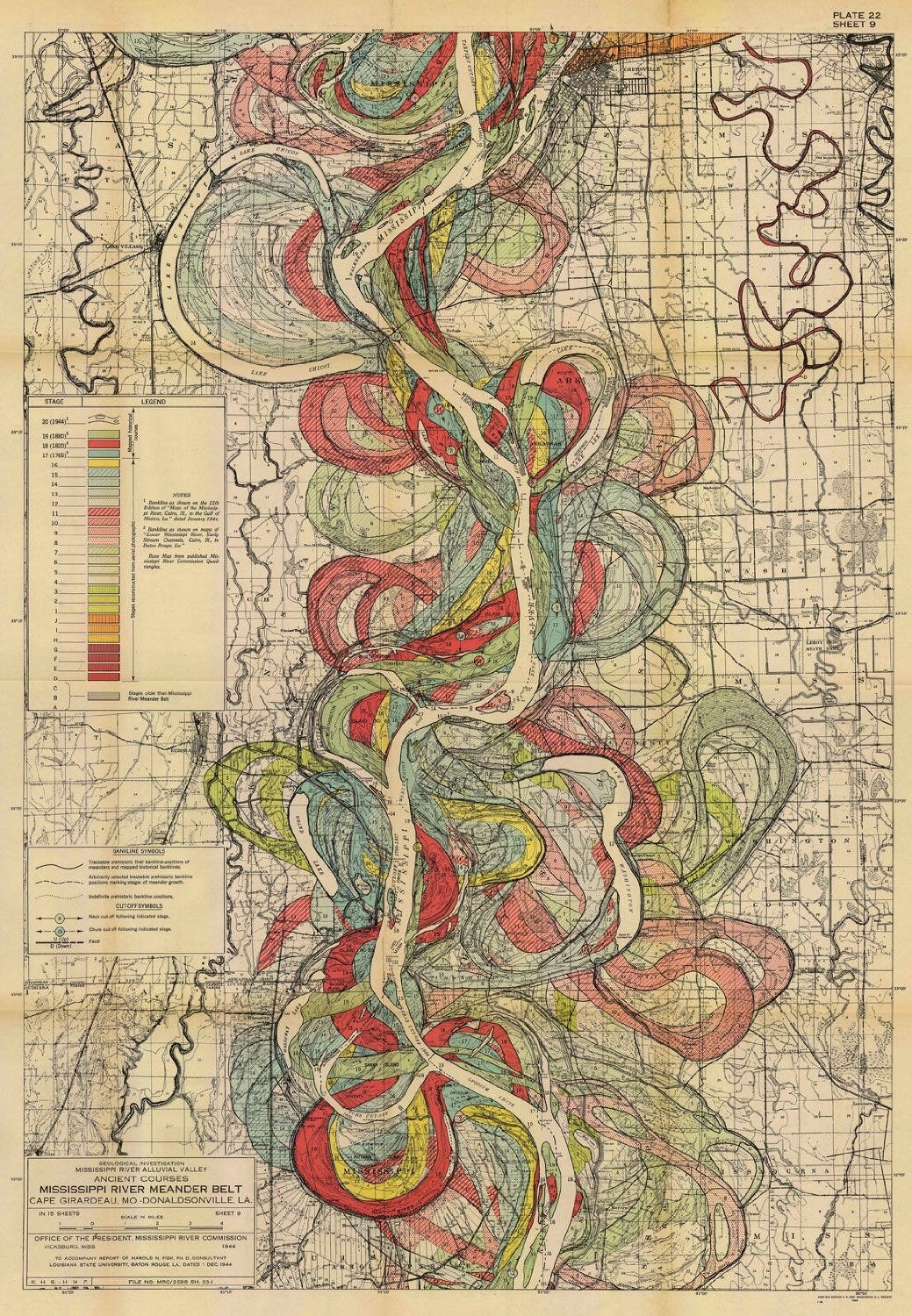

Being a child of the 20th century, I had a hard time seeing history as an impersonal force. Genocide, it seemed to me, is very personal. I also had difficulty with the idea of a predetermined path “ending” in any kind of permanent condition (utopian or not), which seemed at least to contradict the findings of the physical sciences, a fact that would've shocked Marx: that the fundamental state of things is uncertain, that even rivers are not set. They change course over time—on the geologic scale, quite frequently. The undulations of the Mississippi, rolling down the land, look like a trickle of water dancing down the glass in my shower.

It seemed instead that history was more like the weather, or perhaps the ocean—governed at the large scale by innumerable natural forces that pulled against each other, but on the smaller scale bubbling with chaos. I set out, then, to try to understand some of these forces. I read historiography by Braudel and the Annales school, I read global historians like William McNeill, and of course Jared Diamond, all of whom identified currents and tidal forces in the ocean of history.

It seemed only one thing was certain.

Just about everyone these days is a grumpy old man, obsessed with decline and convinced of its inevitable loom. More than that, the acolytes of this cult, who are everywhere, are deeply suspicious that anything could ever be as good again.

The problem with the cult of decline is that it presupposes a certain fixed point of view—the origin of Browne’s parabola—and is deliberately blind to all others. In the case of Somerleyton, the house is falling apart, yes. But from the standpoint of the trees, things have never been better.

In that sense, the cult of decline is hopelessly partisan. The fall of the Roman Empire is the inescapable pivot of Browne’s arc, but the dynastic cycle in China has no pivot, only an axis, and there is an unbroken contiguity of past and present in places like Japan and Dravidic India. History, it seems, has all these shapes: parabola, sine wave, line.

From the point of view of a barnacle, the whole of the ocean seems to rise and fall. Stand long enough before the tides and eventually you’ll see the erosion of the shore. But what are the tides from inside the ocean? The erosion of one beach leads to its deposition elsewhere. What is decline but the birth of something new?

The cult of decline worships a tautology, a cognitive bias, a bank run. If you believe things are failing, then you won't expend the energy necessary to sustain them, and they will fail. In a universe like ours, dominated by the Second Law of Thermodynamics, some creative vitality is necessary to sustain anything, even a good mood.

The Roman Empire didn't succumb to insurmountable tidal forces. There was no tsunami of decrepitude that wiped it away. Everything it faced at the end—wars, barbarians, epidemics—was something it had conquered more than once before. The difference was that its people no longer cared enough to overcome them. They believed it was over, and so it was.

But far from being an end, the Empire fell and something even more miraculous took its place—everything, in fact, that we now lament losing.

Where is the tragedy?

What is certain, of course, is change, which is venerated by another, equally misguided cult, as convinced that everything is bad now as the cult of decline is that nothing will ever be as good again.

It isn’t that some things get better and some worse and it all evens out. If war breaks out and you are killed or driven from your home, things are very much worse for you. But from the standpoint of the whole show, we can’t know. Things may get better. They may get worse. But never forever. There’s no war not halted by peace. There’s no peace not halted by war.

Western culture is boiling, certainly, which looks like disintegration from inside the pot. What once congealed is now in froth. That which was will no longer be.

A moon disintegrates and becomes something rarer still.