On a dusty shelf of some old store, a Baedeker, left in our universe by a traveler from another, waits to be discovered by that most patient and intrepid of explorers: the reader.

It was the accidental death of the poet Arthur Northbourne Pirkin that brought the ritual of dawn, called the Summoning of Ecstasy, to the attention of wider civilization. In fact, he was obsessed with it, finding it at once carnal and sacred, obscene and sublime, and he spent the last 23 years of his life in a relentless search for its origin, which he believed to be the first revelation to man. So arcane and meandering was the ritual's history, however, that Northbourne was compelled to record every scrap he encountered, as if the crux of the mystery lay literally everywhere: in the half-remembered anecdota of pensioners, among bits of holy rubbish or the musings of a librarian of nonsense, even every variant of the children’s song, Dorca Darka, which is supposed to derive from a raunchy spiritual sung by ritual attendants before the time of the Tarquins. Northbourne kept it all on whatever material was ready to hand. Stuffed into one of the poet’s four thousand notebooks was a curled piece of hee tree bark on the inside of which was roughly scratched the lyrics “Diddly-hie diddly-day, a month of crackwork for no pay,” which would appear to be a less offensive version of the third verse. Where the bark came from or what connection it might have to the ritual is not clear.

Indeed, so varied and comprehensive is Northbourne’s collection that thus far no one has been able to make sense of it, despite numerous attempts. Col. Menshat of the Presidium of Antiquities Museum famously declared in 1092 that Northbourne was not only mad but had made madness a contagion, that the Summoning of Ecstasy was a depraved act by a barbarian culture and that was the end of it, that there was no riddle, and that anyone who succumbed to the search was a mentally gelatinous nincompoop. But many scholars are not so sure. Northbourne was, after all, an accomplished poet in his youth, and there is a kind of overlapping structure to his notes, not unlike ripples passing though each other in otherwise still water. A course on Northbourne’s Ecstasy, as the notebooks are collectively called, is taught every year at the Imperium University. (On the other hand, as far away as Margos, the Merigorn word for any overt and intentional complexity is pirgan.)

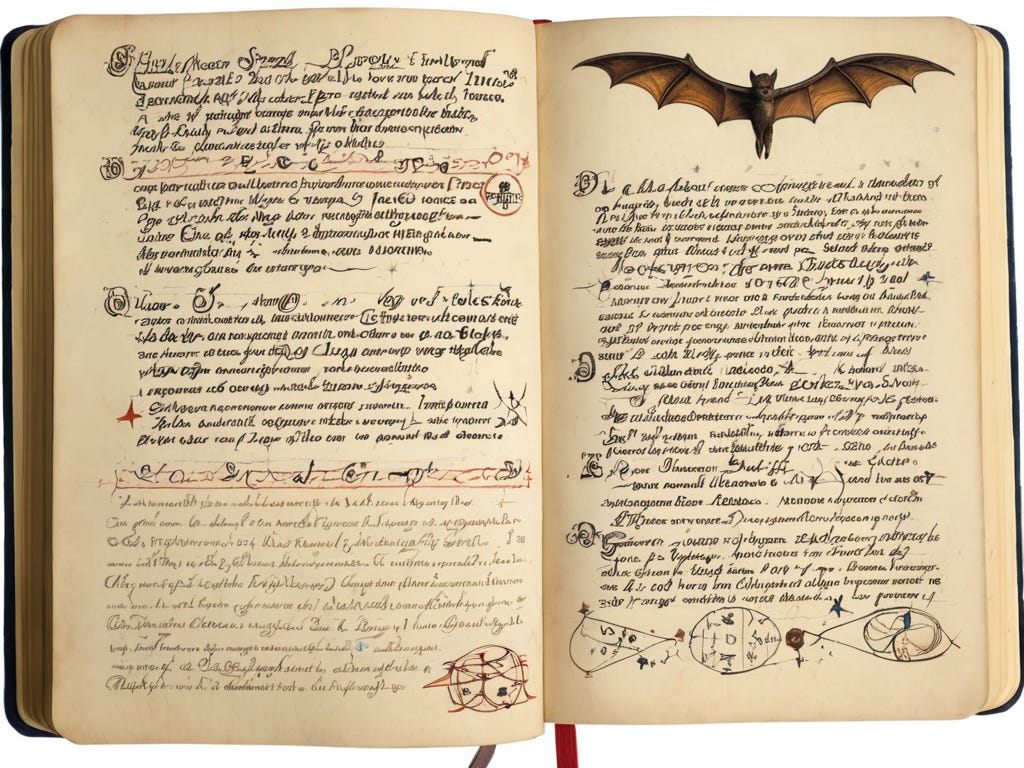

The 47 headings in the notebooks include: Lists and Things Impossible to List, Waltzes, Errant Calligraphy, Thoughts I Do Not Own, The Emperor’s Laundry, and Stella/Stelae. The latter includes a number of large chalk rubbings of rock sculptures of the Lower Gasfan Basin mapped in Northbourne's hand to various constellations visible only from Oth, although it should be noted that it also includes a great many scraps having nothing to do with carvings or stars but perhaps hinting at a connection, such as the severed wing of a small batlike creature called a ding, one of only seven entries in the notebooks not made of words.

Northbourne’s most famous observation was that the gods of Oth do not sit atop each other as they do on every other world. On Margos, for example, pantheons form a kind of geologic strata, with the lived gods resting above a collection of imports from the Salisian conquest in turn resting above the old gods, who subsist only on a few persistent rituals, such as the cutting of the cord, that everyone on Margos practices without really knowing why. On Oth, however, old gods are still called by their first names and they mingle with new and immigrant alike. A man in clothes of unhewn fiber can don a porpal-shell mask or buy his groceries at market without ever realizing the contradiction. “It is as if,” Northbourne observed, “the gods of every world retire to Oth. Every faith is practiced and every practice is a warm memory.”

Ironically, the dawn ritual is far less discussed in wider civilization than the notebooks Northbourne collected on it, perhaps because mere mention of the Summoning causes people to blush. Sketches of the ritual by a traveler were turned into woodcut prints Ghemt the Elder, reproductions of which might occasionally be found in the bottom bin of any shop that sells old books. One print in particular lives on in the public consciousness and variations of it often appear on punk rock posters, in wall art, or as erotic kitsch.

In 1204, Darat Tan published her award-winning novel The Emperor’s Laundry about a witty and incisive poet whose lifelong study of an ancient erotic text leads her romantic partners one-by-one to madness, although the cryptic last line of the text seems to suggest it might be the narrator herself who has gone mad.

The Rape of a Mysterian

On a dusty shelf of some old store, a Baedeker, left in our universe by a traveler from another, waits to be discovered by that most patient and intrepid of explorers: the reader.