Dear aspiring novelist,

Thank you for your letter. I don’t wish to offend, but I’ve been asked that question before, and I’ve learned something like the following is the best advice I can give. It may or may not be good advice.

No one is born knowing how to write a novel. Some spring writers succumb to the idea that if they just work hard enough—or want it bad enough—they can create something compellingly good their first time at bat. Probably not. Imagine a student-surgeon believing that. Probably we’ll need to practice, where practice doesn’t mean writing and rewriting chapters. A surgeon isn’t a surgeon because she’s good at cutting, and we’re not chapterists. We’re novelists. That means we’re probably going to have to write a few novels before we’re good enough to be paid. An author’s first novel published is rarely their first novel written. There are exceptions, but probably you’re not one. I wasn’t either.

Still, I’m glad you’re writing. I encourage everyone to write a book. I even convinced my elderly father, who blames me entirely for the cowboy trilogy he’s almost finished. I think there’s value in writing, as there is in learning a musical instrument or a foreign language, even where you don’t intend to become a musician or interpreter. But there’s a difference between learning the guitar for personal growth and playing it professionally, where you expect people to pay you for the pleasure of listening, just as there’s a difference between running a marathon for the challenge and competing to win prize money.

There’s something about writing a novel that makes people think it’s not like those other things, that it’s something they can sufficiently master the first time out, whereas you hardly hear anyone say they’re composing a symphony and hoping their first attempt will be played by the Royal Philharmonic.

I’m not surprised you are struggling. The bad news is it’s not immediately going to get easier. The good news is the struggle is where you learn.

Definitely don’t write anything you’re not excited to write. Our words are our babies. If you’re not excited about yours, no one else will be by a long shot. Readers are not forgiving. And they can smell a cheat. It’s hard enough to convince them to give you a chance. You don’t get a second. And remember, if you’re going to do it professionally, you’re not going for the sale. The few dollars you make isn’t even going to buy you a coffee. You’re going for the recommendation, and you’re not going to get it if you know or even suspect a big chunk of your book is a slog. That’s point number one.

Point number two you already mentioned: editing. There is no version of this book that won’t require major rewrites before it’s worth reading. Accept that in your bones, and accept that you can’t get to the second draft until the first is done. So, finish it. If you’ve written yourself into a corner, or into a general malaise for the story, skip to the part you are excited about. Often, the mere act of writing spurs more, but either way, finish the draft, even if you suspect there are holes. You can address whatever needs addressing in the rewrite. It’s your first time, so you may need several major rewrites, where you cut your dear to the bone, before you can’t make the story any better. We learn by doing, so regardless of the outcome, your second novel will be easier. People may even pay you for it.

Sincerely,

me

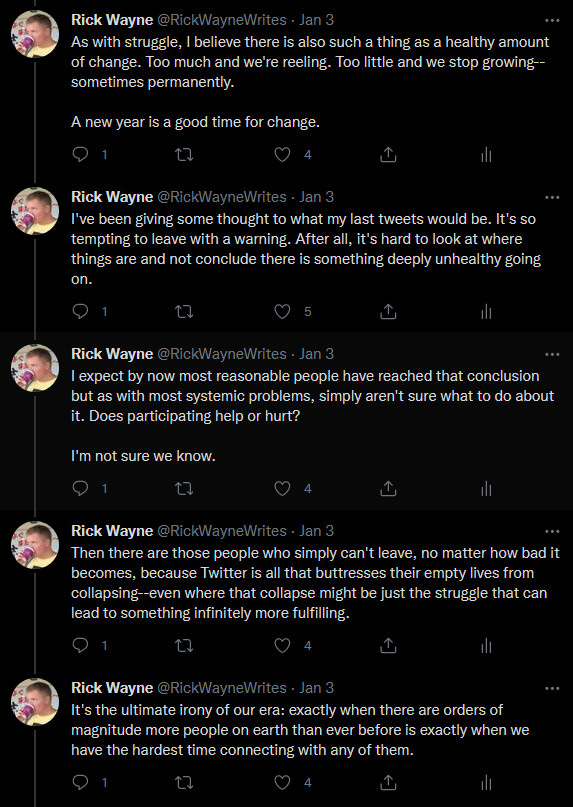

I heard from a pair of readers recently, which is a rarity for me. To the first, I sent the text above, which is a version of a response I’ve used once or twice a year for the last several years. I suspect it’s not what most folks want to hear, but it is the best thing I can tell them.

To the second, I sent a thank you for this:

I’ve said for some time that if I’d had a serious marketing budget for that series, it might’ve taken off. The problem—or at least one of them—was the format. There’s not a ready market for a series of novellas, or at least there’s not perceived to be, which is why it would’ve been pointless to query it.

These things are hard.

Last week, my life changed irrevocably, and not for the better. I’m not able to give any details because there is likely legal action pending. Suffice it to say, I was accused of something I did not do, but I was punished for it anyway, solely based on my race and gender.

That is not speculation. I was told that explicitly at the same time I was told I would not be given a chance to rebut. I was not contacted at all, in fact, until after the decision had been made. One moment, life was normal. The next, I was slandered and thrown out.

That night, lying in bed, I felt cold. My wife, crying next to me in sadness and frustration, suggested I was physically in shock. I suspect she was right.

It was her birthday.

We live in Kafkaesque times. Lots of people, convinced they are good, don’t care to consider the consequences of their actions, as if the road to hell were paved with anything else. I thought that by leaving Twitter, I would be more or less insulated from it. But there is no insulation. It is everywhere.

Writing books is hard. Marketing them is hard. Life is hard. That’s not simply an observation. It’s a mathematically provable fact.

In 2014, on a visit to Los Angeles, I got a very strange tattoo: the Second Law of Thermodynamics surrounded by the ourobouros, or snake devouring its tail. I call it a Western yin-yang, and I permanently marked it on my skin as a reminder that such things happen.

I like that the Second Law isn’t an equation. Equations simply say that two things are equal. It may be interesting to know that, but in the end, every equation is reducible, in a philosophical sense, to 1=1.

The Second Law isn’t even a proper function. It’s a boundary condition: a barrier. The Second Law of Thermodynamics is the scientific expression of man's expulsion from paradise. It’s the reason you have to work because it’s the reason you have to eat, wear clothes, vacuum and dust your house, fix your car, have health insurance, and generally put effort into anything and everything, because order can never come about on its own. It always requires effort.

The Second Law is also the reason we grow old and die, and why we can't reverse time, like running back a tape, and go back to fix our mistakes. We can only go forward, bleeding chaos like a wake.

It's very Shakespearean. If Hamlet were alive, he would go about quoting the Second Law. I'm sure of it.

To be or To be

The symbol that surrounds the Second Law on my arm has many meanings, which is partly why I chose it. It's a perfect counterpoint to the precision of science. But more than that, the ourobouros defies the Second Law. If a serpent really were eating itself and then using the digested tissue to regrow what it lost, it would continually lose energy to heat, meaning it could never recover everything it ate and the "system" would wind down to death.

And yet, the serpent doesn't die. As a circle, the symbol of infinity, it goes round and round, eternally fulfilled by the mysterious source from whence all comes, including the Second Law.

So, here we have the universal opposites: infinity and the finite, fact and superstition, science and magic, terror and meaning, the end and the beginning, the barrier to paradise and the hope of its return. Between those dancing ends, the poles of possibility, lie all things. That's where I am and where you are, on the far side of the barrier struggling to do the best we can.

I don’t know what will happen next, if what stained me last week will become permanent. I also don’t know when I will be free to discuss it. I do know that I may be silent for a while. I have a lot of work to do to fight this.

But at least I have my wife, who has been wonderfully supportive (so much so that even my father commented on it). And of course this guy.

Here is this month’s picture of Henry.

That’s it for this time. I’m glad you’re here.

I was thinking about you today, and look, here you are. I quoted a friend some writing advice that had been lodged in the back of my brain. I wasn't sure it was from you, but it could have been. Best wishes from the ether.

FWIW I’m glad you’re here, too.