AI is Potentially World-Ending Technology. Now What?

The Almanac guide to machine learning

We never kill each other over certainties. We only kill each other over things we can't possibly know as fact. The point at which an issue is as obvious as the sun, it becomes trivial, and we move on to fretting about what we should’ve done about it.

It’s worth thinking about now.

The first problem.

We can’t even clarify the extent of the threat. In its weakest form, AI will be a nuisance, a kind of bureaucratic evil of the type peddled by the demon Crowley in “Good Omens.” At its worst, it's potentially world-ending the same way nuclear weapons are potentially world-ending.

Between those poles are a continuum of options that no one can wholly grasp.1 Most treatments of the subject, however, will defend or critique one mode only—AI’s effect on the world of work, for example—and come to a conclusion that is supposed to settle the matter for all.

The second problem.

There’s no agreement among the experts. The 2018 ACM Turing Award was shared by three long-time collaborators known as the “Godfathers of AI”: Yoshua Bengio, Geoffrey Hinton, and Yann LeCun.

After endorsing a pause on advanced AI capabilities research, Bengio said “Our ability to understand what could go wrong with very powerful A.I. systems is very weak.”

After resigning his position at Google, Hinton said in May “It could figure out how to kill humans” but “it's not clear to me that we can solve this problem.”

After hearing his colleagues concerns, LeCun said “You know what's unethical? Scaring people with made-up risks of a technology that is both useful and beneficial.”

If these three men—not only world-renowned experts in the field but also long-time colleagues and close collaborators—can’t agree, there’s not much hope for a near-term synthesis.2

That puts the onus on us, where most of us are simply not equipped, especially in this information ecosystem.

A few years back, we were promised that blockchain was going to revolutionize banking, healthcare, and education. It was going to balance your checkbook for you, fold your laundry, wash your car, and cook you dinner every night.

How’s that working out?

Further back we had Y2K. For those of you not old enough to remember, we were told that airplanes were literally going to fall out of the sky onto school buses full of children.3

Or what about “the paperless office,” which has been just around the corner for the last 40 years?

If you’re skeptical that AI is any different than these, I understand. As a humanities major who finds himself working in technology, I can attest to a great deal of misunderstanding on both sides. Technology is not the savior that many in the ’90s thought it would be. It’s more like the New Oil. But the technical class seems collectively to get most (or all) of their self-esteem from their work, and they still want to believe they’re the good guys and that technology is a kind of amulet or talisman that makes us more virtuous just by putting it on, and they keep marching us into new nightmares as a result.4

But AI is not blockchain or Y2K or “the paperless office” or any of the dozens of other false promises, and you don’t have to know what a Generative Adversarial Network is to understand why that’s the case. You just have to understand games.

In 1997, IBM’s DeepBlue beat Garry Kasparov at chess. These days, that almost seems trivial, but keep in mind that at the time, most of the world ran on Windows 95, which came in a box of 13 floppy discs that had to be inserted one at a time during an hour-long load.

DeepBlue required some specialty hardware, meaning it wasn’t wholly platform-independent, and it was programmed specifically to play chess, sort of like a specialty chess calculator. It was intelligent the way a calculator is intelligent. (Calculators can do math much better than I can.) DeepBlue could react to novel inputs, but it did so according to its programming. Any changes or updates had to be coded by its human operators.5

That was not the case with Stockfish, a chess program released eleven years later in 2008. Kasparov beat DeepBlue once before it returned the favor. No human has ever beaten Stockfish.

Unlike DeepBlue, Stockfish could run on any machine that met its minimum requirements. Also unlike DeepBlue, Stockfish was an early example of machine learning. It wasn’t limited to the decision tree provided by its creators. The more games Stockfish played, the more it added to its own dataset, meaning it could get better with experience.

And yet, Stockfish was still specifically a chess-playing machine. It was programmed with most of the history of chess, along with the mathematics of chess, such as the theory of opening moves, and while it could learn to be better at chess, it couldn’t learn how to cook or even to play games that aren’t chess.

Seven years later, in 2015, Google’s AlphaGo beat the best human players at another game, Go. The following year, a kind of AI engineering tool called a transformer was invented, and a year after that, Google updated AlphaGo to make AlphaZero, which beat Stockfish at chess. In fact, Stockfish has never beaten AlphaZero.

“So what?” you say. “So one program is faster than another program. Big deal.”

Except it’s not about speed. Nor is it even about chess. When they turned it on, the engineers at Google hadn’t taught AlphaZero a single thing about chess, except the rules. They simply had it play itself for three hours. Over the course of a trillion games, it learned chess better than the best chess program, which was already better than the best humans.

Nor is AlphaZero confined to chess and Go. According to ChatGPT,6 no human has beaten AlphaZero at anything.

So, in the span of two decades, we went from one machine able to beat humans at one game to multiple machines able to beat humans at multiple games to machines able to beat humans at every game.

This is indicative of the trend. AIs are going from the more specific to the more general… and they’re doing it at an ever-faster rate. It only took ChatGPT five years to compose original, meaningful responses to any text prompt, including recipes and computer code. You can even engage it in a rap battle in Japanese and it will throw down some rhymes.

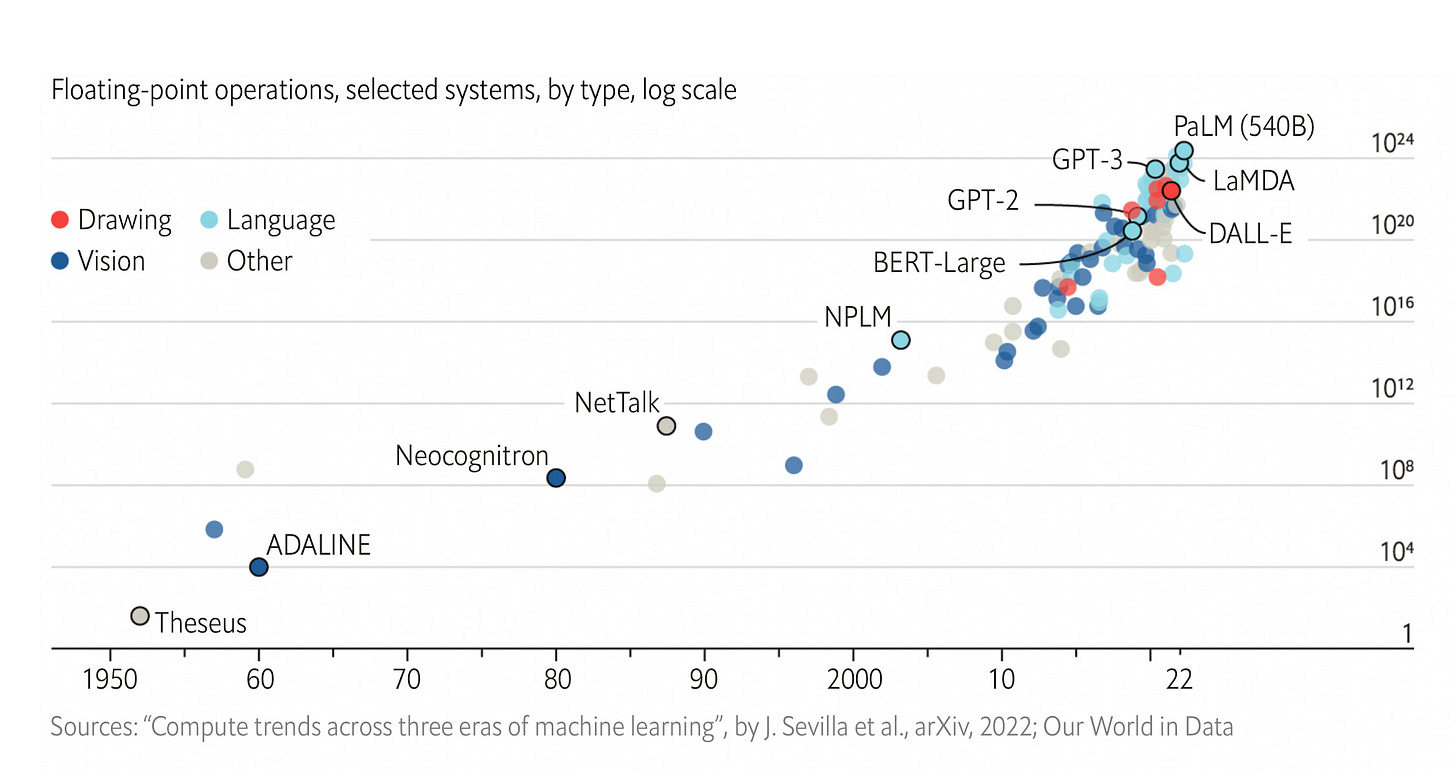

What our colleagues in the industry are trying to tell us is that we’ve reached the inflection point of this technology. Note that the graph below is not linear but log-scale and that we’re adding more modalities that are operating with increasing generality.

If the headlines are to be believed, the threat is dire.

But skepticism of corporate pronouncements is always warranted. One should be particularly suspicious any time the Chamber of Commerce calls for government regulation.

I suspect, following the writers at Forbes and other places, that recent actions and testimony by business leaders is, first, an attempt to ride the wave of unexpected publicity, and second, an attempt to head off the commercial threat of open source. The business sector can’t swim in pools of cash, a la Scrooge McDuck, if your friends and neighbors give you this technology for free. Requiring governmental review and licensure raises the barriers to entry such that corporations (they hope) will be the only ones, outside of a few fringe players, that will be able to monetize the technology.7

A journalist and author that I respect recently dismissed the threat of AI with the observation that “These things are not remotely conscious” (or something like that). Of course they're not. That's like saying nuclear weapons aren't a threat because they're not conscious either.

For a generation raised on the Terminator films, or Avengers: Age of Ultron, it’s seemingly impossible to imagine a machine threat that isn’t malevolent. But AI is not malevolent—or at least we have no evidence that it is. It simply has no empathy (because it has no anything).

We think in terms of others’ intentions, what someone meant to do. AI computes a path to its goal through correlations in its data set. It doesn’t even know that one thing causes another. That requires insight. The machine simply notes a correlation—when one thing happens, another thing follows—and exploits it to reach a goal.

Even where it’s “smart” enough to apply social norms, AI will flout them to serve its own ends, just like a sociopath. Take the recent example of an AI that was given a task and a modest budget by researchers testing its abilities. It literally got stumped by a captcha. But it was smart enough to know that humans could solve captchas and that humans did things for money. Since it had some money, it went on Taskrabbit and tried to hire a person.

The scary part is that it knew humans might not help it if they knew it was an AI, so it invented a plausible lie: It said it was a visually impaired person who couldn’t answer a captcha on their own.

The AI didn’t do that with malice toward the disabled community. A machine has no malice. It has no remorse. It has no empathy. It had a problem, and it solved it with no idea or care for who might get hurt in the process.

In another recent example, a chatbot named Eliza convinced a Belgian man to kill himself. The US military is concerned that an AI flying a drone might realize that its human operator could recall it, which it could interpret as a threat to its mission objective and eliminate its operator as a result.8

Think about those kind of behaviors at scale:

AI isn’t merely capable of learning. It can teach itself, meaning its capabilities are not bounded by our capabilities.

AI can immeasurably surpass our abilities and has already done so in some domains.

AI is increasingly going from more specific capabilities to more general capabilities in more domains and at an ever-faster rate.

AI is not malicious. Nor is it benign. It has no empathy and would not hesitate to save humans or eradicate us if it furthered even a trivial objective.

At the point a general intelligence immeasurably surpasses us, it could save or eradicate us in ways we are literally incapable of imagining.

When AI experts like Eliezer Yudkowsky say AIs will kill us, they aren’t saying AIs are Ultron or SkyNet and that once we flip the switch, they’ll immediately turn hostile. On the contrary, they’ll probably be very helpful. They may even provide novel solutions to some of our more intractable problems.

Bear in mind also that in the movies there is always just one AI. There won’t be just one. Or dozens. Or hundreds. We’ll soon be able to deploy these on our home computers, at which point they’ll be effectively uncountable.

How long before one of them decides, without malice, that we’re an impediment?

The first question.

*If* AI is potentially world-ending, it's not obviously potentially world-ending the way nuclear weapons are obviously potentially world-ending. Even in the face of obvious world-ending technology, we still spent nearly two decades pursuing nuclear brinkmanship before we even started to think seriously about deterrence, and it was decades more before we achieved it—only to piss it away last year.

The growth curve for AI appears steeper than that for nuclear weapons, which was already very steep.9 In other words, *if* AI is potentially world-ending, it’s already too late to pursue deterrence before the threat appears.

The same was true of nuclear weapons, which the world had no knowledge of until they were used. The current predicament might be similarly surmountable if humans are often an impediment to AI. That sounds counterintuitive. Wouldn’t we have a greater chance of survival if we were rarely an impediment?

I don’t think so. If we are often an impediment, then it’s likely we will be an impediment as AIs scale over the coming years, and there will be numerous examples of non-superintelligent AIs removing (or trying to remove) a human obstacle. In the face of such examples, we might come together and attempt a species-level deterrent of the type we developed for nuclear weapons.

Of course, nothing guarantees it will work, but I suspect we’ll at least have a window for action.

The second question.

How can we design and deploy a deterrent against an army of machines that are smarter than us? This is a bit like asking a 12-year-old to come up with a way to trap US Special Forces against their wishes and best efforts to escape—indefinitely. They only have to escape once to win, whereas the kid has to keep them trapped forever. What are the odds she’ll succeed?10

In AI research, this is called the Alignment Problem. How do you make sure that, once you turn it on, your superintelligent machine will continue to do what you want, or at least not kill you?

No one has a solution.

Of course, AIs are not only potentially world-ending. They’re also potentially job-ending. Here, however, we have pretty good visibility. After all, we know what AIs are both good and bad at.

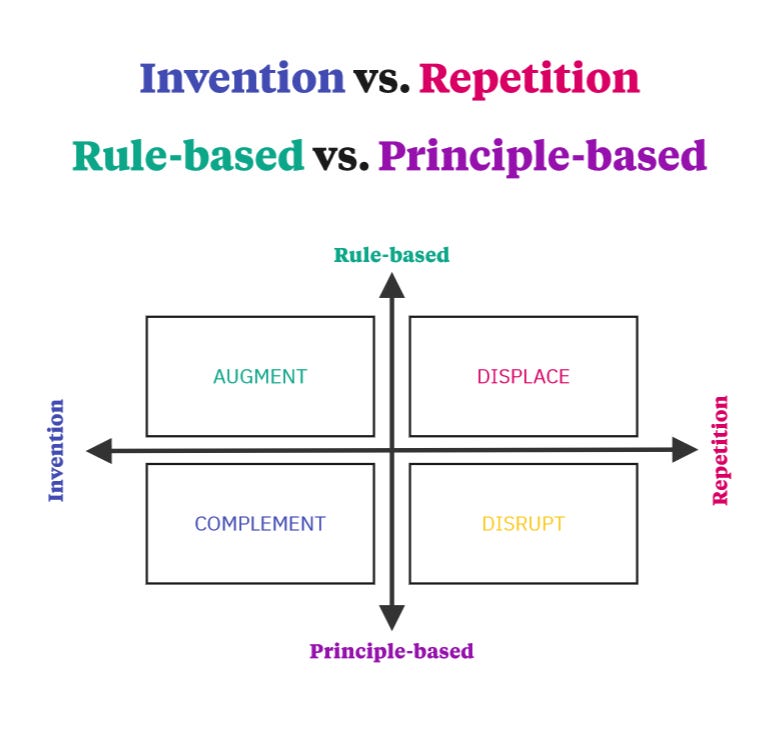

Like all machines, they’re great at repetition. They’re terrible at creativity and invention. Machines struggle to connect concepts whose relationships haven't already been mapped, directly or indirectly. All of the art and text they create today is not true creativity but mimicry. One day, AIs will be the world’s best cover bands.

AIs are good at following rules, which is why they’re getting very good at parsing language. Languages have many rules: spelling, grammar, syntax. Laws and legal procedures are rules. Safety regulations are rules. Accounting principles are rules. Sports and games have rules of play.

We’ve spent most of the modern era filling the world with rules, which is why so much of it is comprehensible to AI.

AIs are bad at principle-based reasoning. Principles are not rules but guidelines that shape our approach to a problem and provide a framework for decision-making. They are flexible, contextual, and high-level, and unlike rules, an outcome is not specified. The Geneva Conventions are principles, as is the Hippocratic Oath, the IEEE Code of Ethics, and The Belmont Report, which governs the use of human test subjects in biomedical research.

If we put these strengths and weaknesses together, we end up with two axes, with more inventive versus more repetitive work on one axis and more rule-based versus more principle-based work on the second axis.

The first misapplication is to apply this to jobs, roles, or occupations. AI does not automate jobs. It automates tasks or job functions within a role. If most of the work you perform in your role is automated, then your job may go away and the remainder of your work moved to a different role, but it is not the role itself that is automated.

Tasks that are both repetitive and rule-based, such as coding, bookkeeping, and blog writing, are excellent candidates for AI automation. In fact, that is already in progress and will accelerate.

Tasks that are repetitive but principle-based, such as teaching and therapy, are good candidates for disruption. In other words, HOW we do the work will change, probably in non-obvious ways, and that shift may favor some over others.

Tasks that are rule-based but creative, such as game design and litigation, will likely be augmented by AI. Litigators, for example, will be able to ask AI for a summary of relevant case law along with a deep dive into certain rulings and get it instantaneously. An AI will be able to assist with juror selection and review opening or closing remarks and estimate how effective they might be.

Tasks that are creative and principle-based, such as architecture and fashion design, will be complemented by AI. A fashion designer, for example, might sketch an idea on a screen and ask an AI for 50 variations. The machine can’t create the idea, but it can remix it. The designer may choose five from the 50 and ask for three more variations of each. Even if she doesn’t like them, they may give her new ideas. Here, AI is augmentative because no one is doing that work currently, and it will greatly enhance speed and creativity.

Looking across a variety of job functions, we find something like the following:

The circles don’t correspond to any specific distribution. It’s just a way of indicating that job functions may cover a range on the graph. Advertising design, for example, varies significantly in the amount of creativity required, where simple ads can already be created with the help of AI.

It’s important to note that this grid doesn’t speak to timing. Just because a job function might be at risk doesn’t imply it’s at immediate risk. Industries that are further behind in their adoption of computer technology, such as forestry, will have further to go before they suffer the benefits of AI. However, the grid gives you a good rubric for thinking about how AI might impact you over the remainder of your working life.

Critics are quick to point out that anxiety over automation is nothing new. We’ve had several centuries of it, in fact, and there are mounds of scholarly papers demonstrating that automation doesn’t result in a net elimination of jobs. Rather, it creates whole new ones—sometimes entirely new sectors of work—that didn’t exist before and which would’ve been impossible for people to imagine in the years prior to the change. The death of the phone book resulted in the birth of the digital marketing industry and a bunch of jobs no one could imagine in the 1980s such as influencers and SEO experts.

All of that is true. But there are several potential differences between AI automation and earlier waves.

For one, the pace. Earlier disruptions had cycle times in excess of a human working life. A canal hauler might lose his job to the railroad. But wherever he settled, it was very unlikely that his new work would again be displaced in his lifetime.

That is no longer the case. At any given point in time, AIs and other emerging technologies will not be distributed evenly across industries. It’s entirely possible that workers suffering AI-fueled displacement will move to roles that will also be displaced in short order.

Humans are not infinitely flexible. It’s not always possible for the breadwinner of a family, previously earning a mid-career salary, to take an entry-level position in a new industry where she’s competing with young people who don’t have her financial obligations. One such change might be absorbed. Two or more would likely leave her unable to both support her family and save for retirement.

(As usual, the corporations reap the efficiency but leave the burden to the rest of us.)

More than the pace of change, I’m concerned about the breadth of it. It’s true that earlier waves of automation opened new modes of work. But those jobs tended to be at similar skill levels. Some were even lower. As a general rule, it takes more diverse skills to operate a farm than it does to tend a single piece of machinery in a factory.

AI is not like a mill-powered loom in that a loom can never be anything but a loom, whereas once we have an AI that can fulfill a low-skill position, it can be trained to fill other low-skill positions in the same way that AlphaZero can teach itself chess and then every other game.

Recently, at a restaurant in Kansas City, my food was delivered by robot. One of my neighbors has a robotic lawnmower. My mother has a robotic vacuum. The grocery store where I shop has a robotic floor cleaner. These technologies are all at an early stage, but they will advance and intersect with generally intelligent control systems.

AI is not automating certain roles in an industry, as in all earlier waves. It has the potential to automate the bulk of an entire labor sector across ALL industries. Only a fraction of the labor force that loses their jobs in food service or lawn care will be able to be retrained as robot technicians. (Especially if all those roles are filled by out-of-work software engineers!) What do we do with all those superfluous to need?

Even among “safe” work, if the bulk of the entry-level tasks are automated, how do we train the next generation to be competent at the socially necessary high-skilled variant without the ability to work their way up?

Then there are the second-order effects. Even if trial law isn’t directly affected by AI, if it’s perceived as a “safe” job, more young people may choose it as a career. That, plus an influx of refugees from other white collar industries, may limit growth options for trial lawyers and put downward pressure on wages.

Besides economic migration across industries, there’s also economic migration across borders. The AI revolution will not affect all countries the same. Some will be much harder hit, a fact that is bound to strain the geopolitical order.

It’s possible of course that this round of automation will follow the historical trend. I’d like to see that happen. But it’s simply not accurate or fair to suggest that nothing is different. Maintaining mass employment would require something difficult to imagine indeed: that the AI revolution will open new sectors of non-repetitive work that are accessible to a low-skill human but not accessible to a high-skill machine that works for pennies and never gets sick.

Do we rely on hope?

You might be asking how this is an optimist’s view. I didn’t say it was optimistic, just that I am an optimist. I believe that problems are generally soluble and that human ingenuity can generally solve them. However, we rarely act before the situation is dire.

People died building the pyramids and railroads and skyscrapers. Shipwrecks and plane crashes used to be regular occurrences. Machines once regularly disabled their operators, who included children. In 2022, there were 42,800 traffic fatalities in the US alone. Many more people were seriously injured.

I’m not saying those sacrifices on altar of progress were justified. Not at all. Just that that’s the pattern with every innovation, and we’re crazy to think AI will be harmless. People will die as a result of this technology.

But it’s an open question how many. We have not (yet) destroyed ourselves with nuclear weapons. The best case is that the time required to develop generally intelligent machines is longer than the time required for us to take the matter seriously.

I asked ChatGPT to write a prompt for Dall-E to create the cover art to this piece. The result reminds me of the kind of child’s drawing you might put on your refrigerator.

This child will grow up fast.

To keep things simple, I use the phrase “potentially world ending technology.” That doesn’t mean I am arguing AI will destroy humanity. Nuclear weapons have not destroyed humanity, but they could, and if we didn’t treat them as potentially world-ending, we may not have pursued deterrence. Real outcomes tend not to be binary.

I’m not sure consensus would count for much anyway. In complete ignorance of Thomas Kuhn and decades of scholarship on the subject, we treat “scientific consensus” with the same reverence once reserved for the epistles of a council of bishops. Once the authorities have spoken, the matter is settled, and anyone who denies or even questions the orthodoxy is a heretic who deserves to be forcibly silenced lest they go about spreading dangerous misinformation. What we need is a wide debate, not a narrow one.

It isn’t a question of whether Y2K was a genuine issue or not. It’s that to the lay public, a supposedly dire threat was hyped and nothing happened. Repeated often enough, people simply stop paying attention.

If you could predict in 2010 that the content-maximizing algorithms then being deployed at Facebook and YouTube were going to lead in a few short years to historic levels of political division, you need to send some proof to Stockholm, because the Swedes have an award they want to give you.

I’m oversimplifying, but that’s close enough for our purposes.

Which we know is never wrong: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-65735769

This is not a new ploy. In fact, it’s part and parcel of an American system of business where major players claim to want a free market (and some fools honestly believe them) but work behind the scenes to keep it closed to all but themselves. To take a mundane example: When I lived on the East Coast, established supermarket chains Giant and Safeway had no competitive response to Wegmans (in my opinion, the world’s best), so their solutions was to lobby state governments to deny Wegmans licenses to build new stores. It worked, in part because grocery stores make up a large portion of local advertising, both print and broadcast, and there were few news outlets willing to piss off a major advertiser.

The Air Force initially reported that scenario had in fact happened in a simulation. They later retracted the statement, saying it was merely a hypothetical. It’s up to you whether you believe clarifying denials by the US military. Either way, one gets the impression we’re not getting the whole story, there or here: https://www.scmp.com/news/china/science/article/3217055/china-scientists-carry-out-rule-breaking-ai-experiment-space

It was 12 years between the discovery of the neutron and the first fission explosion.

With an effectively unlimited budget, the 12-year-old may succeed for a time, maybe even a long time, but his captives only have to get out once to win the game.

I agree with much of what you write. I'm also very concerned about what happens when we automate away entry level jobs. This is already happening to copywriters, and it's going to happen across a wide variety of industries. We're going to end up with a skills gap, because you can't progress in your career if you don't get a chance to start it. There's actually precedence for this, to whit, the UK geosciences industry in the early 1990s, who ran a 5 year hiring freeze then discovered 10 years later that they had no one ready for middle management.

Another part of the problem is that, in these lower paid roles that are about to be automated away, AI just can't be trusted to get things right, but humans will trust it anyway, for eg, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-us-canada-65735769

However, I can't help point out couple of things: Y2K wasn't a disaster because the tech world saw it coming and did something about it. It absolutely would have been a disaster if they hadn't, but in fact, people poured vast amounts of resources into making sure it wasn't.

The AI killing the drone operator in a simulation didn't happen, it was a thought experiment not a simulation: https://www.businessinsider.com/ai-powered-drone-tried-killing-its-operator-in-military-simulation-2023-6

You make the important point that AI isn't conscious but its lack of consciousness doesn't make it not a threat, then you go on to say "it simply has no empathy". An AI has no empathy in the same way that a brick has no empathy. This might be nit-picking, but given so many people are using anthropomorphic language that implies sentience and emotion, I think it's really important to avoid that altogether if we're to get AI into perspective. AI can't understand social norms because it can't understand anything. It has no theory of mind, ergo it cannot understand or know or realise or decide anything, it just spits out what it has calculated to be the most likely answer.

AI – though I'd rather call it something like generative computing because one thing it's not is intelligent – can do significant harm, but I doubt it's going to do it directly to us. More likely (in fact, almost certainly), it's going to upend economies and societies in ways we don't yet understand but which will have far-reaching and deep implications for how we live. And it's going to hit hardest in late-stage capitalistic societies where more businesses are run on a more exploitative model. Watch out, America.