My wife is pregnant. The baby is due in January. It will be our first. I can’t be sure, but Mick Jagger might be the only new father older than me. That’s what it feels like, anyway. I’m very aware that my children’s friends will have grandparents around my age. I’m very aware of the gap. I’m aware it may be the biggest in history.

It’s starting to change now, but for the longest time, there were only two points of view you could have on climate change: that it was all a lie dreamt up by Ivory Tower ideologues who didn’t know about sun cycles or something; or it was a world-ending calamity that required us to rip the guts out of everything RIGHT FUCKING NOW.

It’s an era of High Moronics. Think about it. How well do you have to know someone now to disagree with them about even the simplest things, let alone anything that actually matters? If you’re against Trump, it isn’t enough to simply not vote for him. You have to not vote for him with prejudice. You have to disown anyone who won’t disown anyone for voting for him.

That’s not an accident. There’s a reason.

I’ve been thinking about how to shepherd my children through this world, a world I did not grow up in, a world where even supply chains are fragile, a world of pathologized hyper-concern for people not present over those who are.

The simplest solution seems to be: don’t let them grow up in it. Lest you think I’m crazy, that’s basically the advice of the experts. Social psychologist Jonathan Haidt recently published some guidelines for parents, and they include not letting kids on social media (especially girls) before they’re old enough to drive.

I don’t know that there’s a hard line. Every kid is different. But I take the point. The elephant dung in the room is the coordination problem. If your children’s friends are on social media, your children will also be on social media whether you forbid it or not.

Like adult junkies buying their kids weed, parents today seem enthusiastic about getting their children hooked. I’m not sure how we break that. Shame and derision?

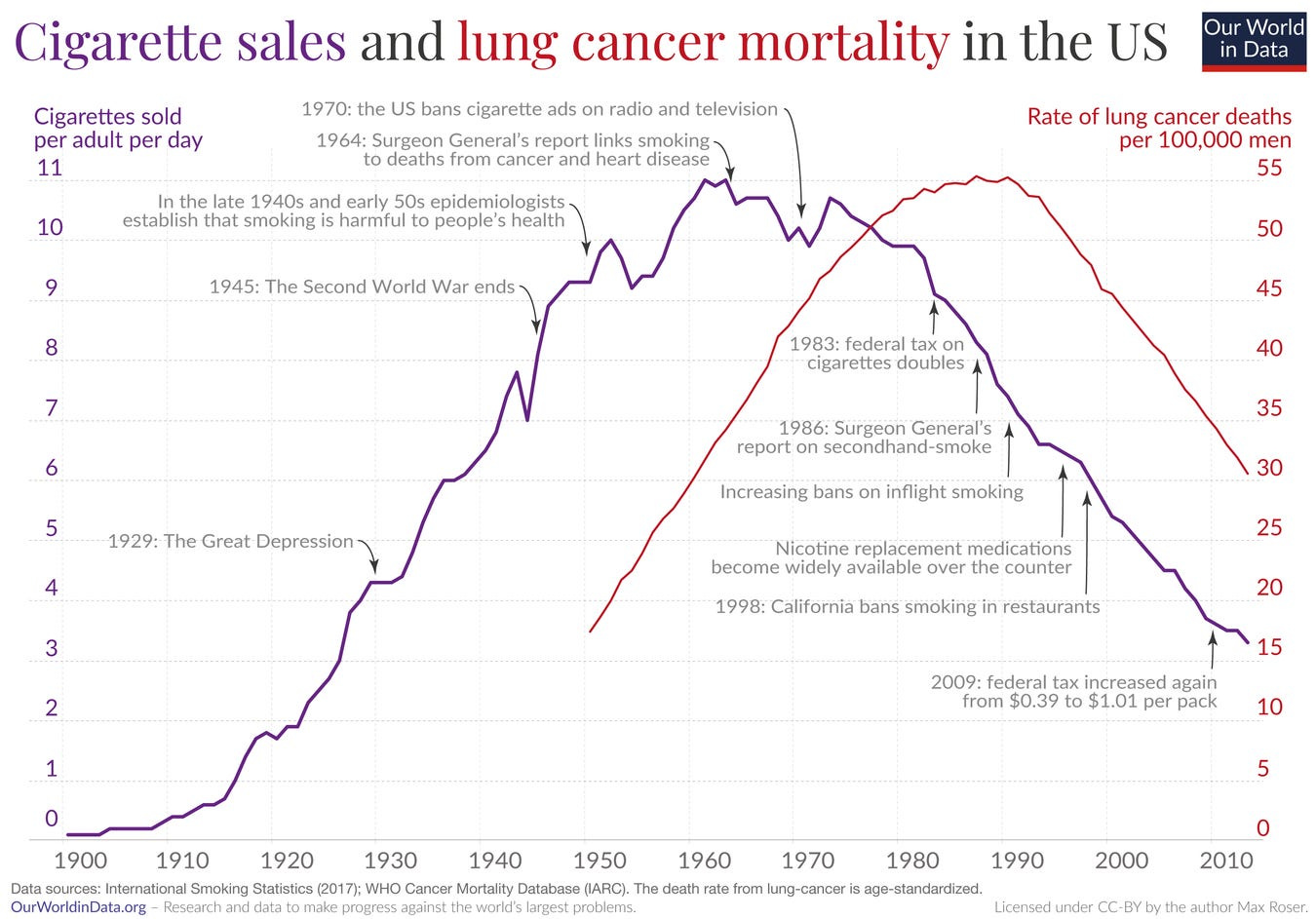

A few years back, it became fashionable to think of data as the new oil. (There is something to that.) The latest analogy is between social media and smoking. The hope is that in 100 years there will be someone very similar to you looking at a graph very similar to this comparing social media use with rates of anxiety/depression/suicide, where those people will wonder why we ever let children on social media in exactly the same way we wonder why anyone ever let kids smoke.

I used to think the battle for civilization was between city dwellers and everyone else, which you see clearly on every granular map of electoral outcomes (which is why everyone uses it). But really it’s deeper than that. It’s between people who live a primarily screen-based life and those who don’t, with lots of folks in the middle. It just so happens that most of the screen dwellers live in large cities.

The screen dwellers are more prepared to accept what they’ve been told because they have nothing to compare it to. They live in a simulation. Everything is constructed and manipulable. The job they do services some part of the simulation rather than anything real. The company that employs them is a digital entity. The people they interact with are as well.

That’s not to say screen dwellers don’t encounter others. But to what degree is their Uber driver or the nameless barista at the coffee shop any more than an NPC in the game of their life?

This is why screen dwellers are obsessed with consensus: the COVID consensus, the climate consensus, etc. Paradoxically, it’s an evolved biological response. In a world devoid of fixed landmarks, where you never know what’s real, there’s a game-theoretic rationality to following the collective observations of the herd. What other measure is there?

It’s a mistake to think the other group, the people that do not live a primarily screen-based life, are mentally or morally superior. They’re not. Most people in history were in that group, and there’s plenty of barbarity to be found there.

It’s also wrong to think of this as the defining difference between red and blue. It’s not. Those categories existed before the simulation and would exist independently of it. (Again, most people are not going to be in the core of either group but somewhere in the middle.)

Rather, it’s that the simulation, being grounded in nothing, allows those groups to diverge more wildly. The people who don't live a primarily screen-based life have something to compare things to, which is why they’ve become increasingly skeptical of what they’ve been told, where it used to be the other way round. When physical commodities like oil were the primary determinants of the economy, the non-screen dwellers were the very same pathological conformists the screen dwellers are today. (Don’t let them tell you otherwise.)

Think of the historical division between agricultural societies (farmers) and pastoral societies (herders) in antiquity. Both had different models of the universe, different pantheons, different virtues, different heroes and monsters, and within each society you had a mix of traditionalists and innovators. There isn’t a mapping of one side then to one side now. It’s simply an example of the epochal scale of the difference, where the screen dwellers are raising entirely new gods.

Traditionally, the resolution was war. I used to think we could avoid it because the simulation and the alternative can occupy the same physical space in a way agriculturalists and pastoralists could not. I saw us fracturing into a multiplicity of lineages, some cultural, some physical. There are already biohacking and transhumanist movements whose offspring will produce something not-quite-us.

This isn’t new, by the way. It’s an aberration for there to be only one extant species of hominin. For most of our lineage, several species cohabited. I expected that would be the case again.

But now I’m not so sure. Or at least, I’m not sure the bottleneck is over. We may still speciate (where speciation could include a non-human successor), just later than I thought.

The simulation is not compulsory at the current time because it can’t be. Lethal force exists outside it. Combat requires real-world skills, which is why the military is not known for having a high proportion of screen dwellers (who would be ill-advised to force a conflict tomorrow).

But all that changes when farming, energy production, and violence are automated. Once robots do most of the work required to bring food and power to the people, even if they are still tended by humans, our last tangible tethers to the physical world will be gone.

Once robots are the more lethal combat force, a reality we are rushing toward, everything can be subsumed by the simulation.

Why wouldn’t it? Even if it were not hostile and merely subsumed what it encountered randomly, what’s to stop it from taking over?

I’m not talking about AI/AGI, by the way. It’s such a hot topic now that I could understand if anyone confused the two. The simulation could exist without AGI. The simulation could direct AGI. The simulation could be directed by AGI. It could also be ended by AGI. Like the three-body problem, the confluence of emergent technologies is notoriously impossible to predict.

But we don’t have to predict the future. If AGI never comes, we’ll still have the simulation because it exists now, mediated by current technology.

If you don’t believe it’s possible for the simulation to control reality, consider we witnessed it overwrite basic mammalian biology in real time. Facts evident since the evolution of sexual reproduction 2 billion years ago were got rid of in less than the runtime of the average TV show. Organizations with staff and budgets came into being based on this new reality. Laws and policies were written and enforced. Surgeries were given. The physical world was altered to reflect the simulation.

It isn’t that those beliefs will persist. They’re already fading. The simulation is polymorphic by nature. When it moves from its current obsession to its next one, reality will be retconned such that the ideas we’re not talking about now and can’t even imagine will have always been on everyone’s mind. (This was the original purpose of the Almanac, to chronicle every end of the world.)

I’m not one to predict the future by running a trend line from the present. There is no surer way to be wrong. But the implosion of social life into the simulation this century has become a singularity pulling everything toward it, right down to our sudden inability to couple and reproduce. That suggests there are massive changes afoot. Demography is history.

Some people think the solution is to go back. But even if we could put the genie back in the bottle (how??), there’s every reason to expect the forces that led us here would lead us right back again. As silly as it sounds, that’s Thanos’s realization in Endgame. You can’t simply reset the clock. You have to do it in a way that prevents it ever from returning. Without the means to do that, the only way out is through.

That leaves me with a quandary. If I’m right, then at some point soon, everyone will have to worship the new gods. (Many, many people already are.) I expect the fulfillment of this change will be comparable in scope to the switch to settled agriculture.

That may sound like hyperbole, but keep in mind that, on an individual level, people who saw others farming and decided to do the same still had a continuity of experience. If you convert to a new religion, you’re still you. What made the switch to settled agriculture or the rise of Christianity so significant was not that anyone did it but that everyone did.

Of course, there will still be outliers. Those that refuse the simulation won’t necessarily be exterminated. They could be living museum pieces like the Amish or people with flip phones—quaint artifacts from a time that is no more and won’t be again.

But make no mistake. The widespread switch to a primarily screen-based life, to the simulation, represents an epochal change for humanity.

Coming from an earlier world, I have to wonder if there’s an alternative. Is there something it is like to live a good human life in the simulation? On the numbers, it wouldn’t seem so. Everyone there appears anxious, depressed, or addicted. But we can no more imagine the future than hunter-gatherers could imagine the Byzantines or the Byzantines could imagine us. Both would be appalled at the things we find most comfortable.

In other words, just because I find the future abhorrent doesn’t mean it won’t be livable. But it makes having children now very poignant. I feel like an ancient fish staring at the shore knowing that’s where the species is headed but unable to lead my offspring there. The most I can do is make them aware of the change and encourage all of you to do the same.

Well, damn.

It is rare to read such sound reasoning.

Rick, this was a great article. I've read it three times now because I wanted to fully assimilate it and see if I disagreed with any of it. Your thinking is sound. I think you're onto something here. There's potential for a fictional story that serves as a metaphor to these ideas if you want to chase it.

When you say 'simulation' are you talking about the people who live in their screens or is that a reference to simulation theory? I think it's the first, but I wanted to ask just to be certain.