"But I thought creatives were safe!"

A case study in improving our thinking about AI

One of the most significant ways—if not THE most significant way—AI will challenge human society is by revealing the self-aggrandizing myths at the heart of many of our assumptions about intelligence, creativity, and what makes us special. Beyond our jobs, the economy, and the global political order, AI’s most lasting disruption may be to our self-image.

Currently, there are two large gaps in our understanding:

Between what we know now and what will actually happen.

Between what we know now and the common understanding.

The precursor to this piece, “AI is Potentially World-Ending Technology. Now What?”, was meant to address the latter. It provided a concrete practical tool for evaluating the potential risk of AI on the remainder of your working life. However, it did not provide an example, and it seems the application is not obvious.

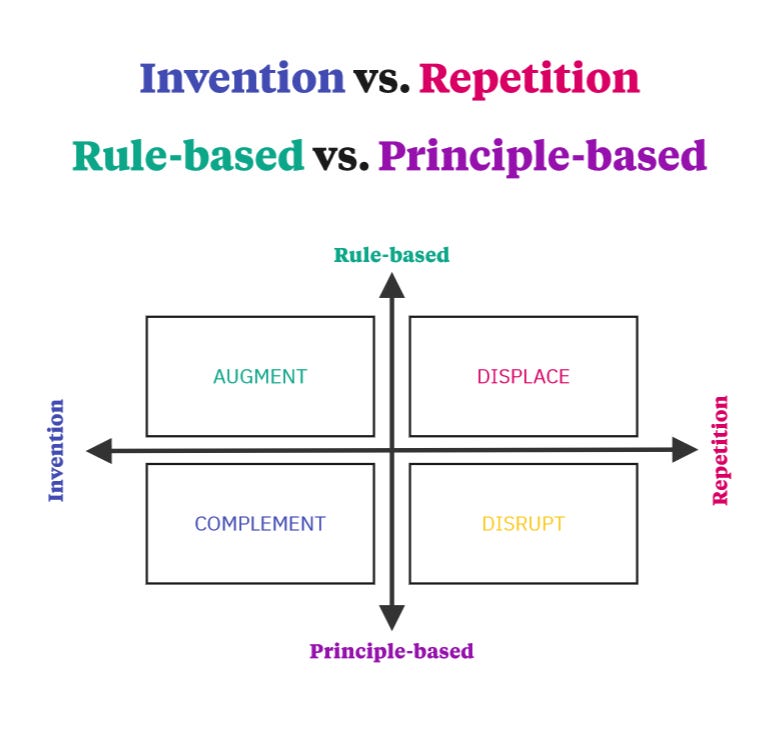

In the article, we plotted the strengths and weaknesses of AI and ended up with two axes: more inventive versus more repetitive work on one axis and more rule-based versus more principle-based work on the other.

The first misapplication is to apply this to jobs, roles, or occupations. AI does not automate jobs. It automates tasks or job functions within a role. If most of the work you perform in your role is automated, then your job may go away and the remainder of your work moved to a different role, but it is not the role itself that is automated.

The following is not nearly detailed enough, but it is a place to start:

For examples and discussion of what the terms mean, see the original article.

Note, the circles in the chart don’t correspond to any specific distribution. It’s just a way of indicating that job functions may cover a range on the graph. Advertising design, for example, varies significantly in the amount of creativity required, where simple ads can already be created with the help of AI.

The same is true of the brands and campaign messages on which those ads are based. Even before AI, if you were not too particular about your company logo, you could find any number of pre-designed ones on stock image sites like Depositphotos.

We simply don’t know the true valuation of such things in advance, which means they are impossible to price. The recent movie Air, on the creation of the Air Jordan shoe line, suggested that Nike paid a student designer $35 (about $250 today) for their infamous SWOOSH. Who at the time could say that was undervalued?1

What is true of advertising and design is also true of work broadly labeled “art.” There are already online libraries of stock art available. Not all of them compensate their contributors, and even those that do often compensate them trivially, meaning most of the images in commercial use were not individually highly valued.

Recently, I've come across several variations of the statement “Creatives were supposed to be safe from AI, but artists are losing work to these tools!”

Unfortunately, that view relies on two fundamental misunderstandings.

First, it presents the issue in terms of occupation and not task. When it comes to the impact of AI on work, precision matters. You may describe yourself as an artist, but that’s not a task. “Character illustration” or “sculpture” is closer to the mark.

Second, that view misrepresents an artist/illustrator's core value-add. Art (with a capital A) may be price-less—most of what we make in a year couldn't be given away—but for-hire character illustration, for example, is fundamentally transactional.

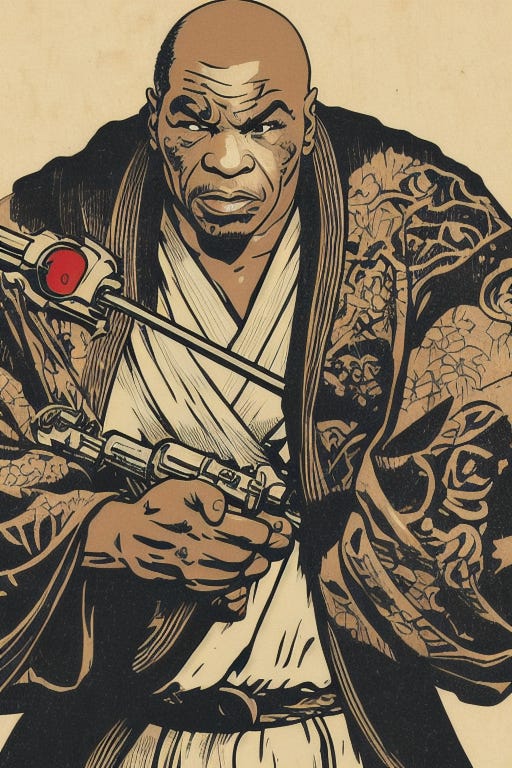

It’s also largely mechanical. The client is buying a depiction or portrayal of an existing idea—zombie Betty White dressed like Rambo and riding a T-Rex; Mike Tyson as a Jedi knight depicted in the Japanese woodcut style.

The Machine at the End of the World as a frontispiece to an early Renaissance book.

The features of the character to be illustrated are often already determined, which means the creative act is significantly complete by the time the artist applies their mechanical ability to translate a text description into an image.2

That can now be automated.

In the case of the top illustrators, clients are also buying their highly distinctive style, which represents an additional value-add, and in a fair world, those people would continue to be able to charge a premium. But as many have noted, AI models are capable of mimicking any style. Several court cases are underway that will decide whether that counts as copyright infringement.3

It should be possible to prevent large for-profit entities from copying an artist’s style without their permission in the same way that it should be possible to prevent large for-profit entities from using a person’s likeness without their permission. But preventing individuals and smaller groups from doing the same, while technically possible, would require dystopian levels of global oversight, enforcement, and control of the type that could easily be abused.

Even if you removed every artist’s work from every AI training set, automation of the mechanical act of visual portrayal is here, or soon will be. In the original article, we noted that Google’s AlphaZero—which beat the chess program that beat every human—was never trained on chess. It was merely given the rules of the game and asked to play itself for three hours, by which time it learned chess on its own.

In other words, rather than mimicking the art in a data set, AI could treat it as a destination and teach itself perspective, color theory, and the rest. (Isn’t that how human artists learn?) Hence, any court victory will be short-lived.

Long before AI, I asked a tattoo artist—who was then giving me a tattoo—how tattoos were priced. He made the prescient observation that there was really no objective way to say that one person’s depiction of, say, a butterfly was worth more than another’s such that the first gets to charge more. The reality, he suggested, was that most tattoo artists—which was everyone not being written up in the industry magazines—effectively charged by size and complexity as a proxy for time and materials, even if they didn’t think of it that way.

There’s no reason why most tattoos couldn’t be printed under your skin by machine, especially those depicting zombie Betty White riding a T-Rex or any other specific image. In my case, the artist literally traced the image onto my skin and then went over it with the needle. A machine could theoretically do it cheaper, safer, and more accurately. It could also tell you that you were misspelling the word “ragret.”

Right now, AI art models cannot handle editing and revision. But as we demonstrated in the last article, AIs are going from more specific to more general capabilities and at a faster and faster rate. It will not be long before they can edit and remix their own work—perhaps by giving one AI the job of generation and another the job of editing.

That means that as a novelist I will be able to work collaboratively with an AI to create original works of art exactly to my specifications without having to know how to draw, and the machine will be able to suggest improvements based on the empirical data of what has worked well for others in the past. Beyond book covers, maps, and character illustrations, I will be able to create my own comics.

Eventually, my own movies, completely without cameras, actors, or props.

So, while it is generally true to say that “machines are not creative,” it is not true that that means artists’ jobs are “safe.” The creative act is not wholly or even mostly in the mechanical manifestation of an image. It can be, but most of the time, the act of depiction is a translation from one medium—a text or speech description from an art director, for example—into another—ink and paper, or even sculpture.

Chinese artist Zhelong Zhou creates absolutely beautiful digital sculptures. The ability to 3D-print them in comparable materials isn’t here yet, but it will be. In the meantime, we can 3D-print casts that can be use to make them, meaning its getting easier and easier to make our fantasies real.

That, by the way, is one of the key ways we are not manifesting a cyberpunk dystopia but an opposite kind. The cyberpunk writers got it backwards. Humans are not invading cyberspace. Cyberspace is invading the real world. Narrative warfare will become indistinguishable from physical warfare. Winners always wrote history. Now they will determine reality itself.

Not every human is creative, but many more are than have the physical skill to draw. Artists are now competing with all of them in the same way that the invention of the chainsaw meant many more people could be lumberjacks.

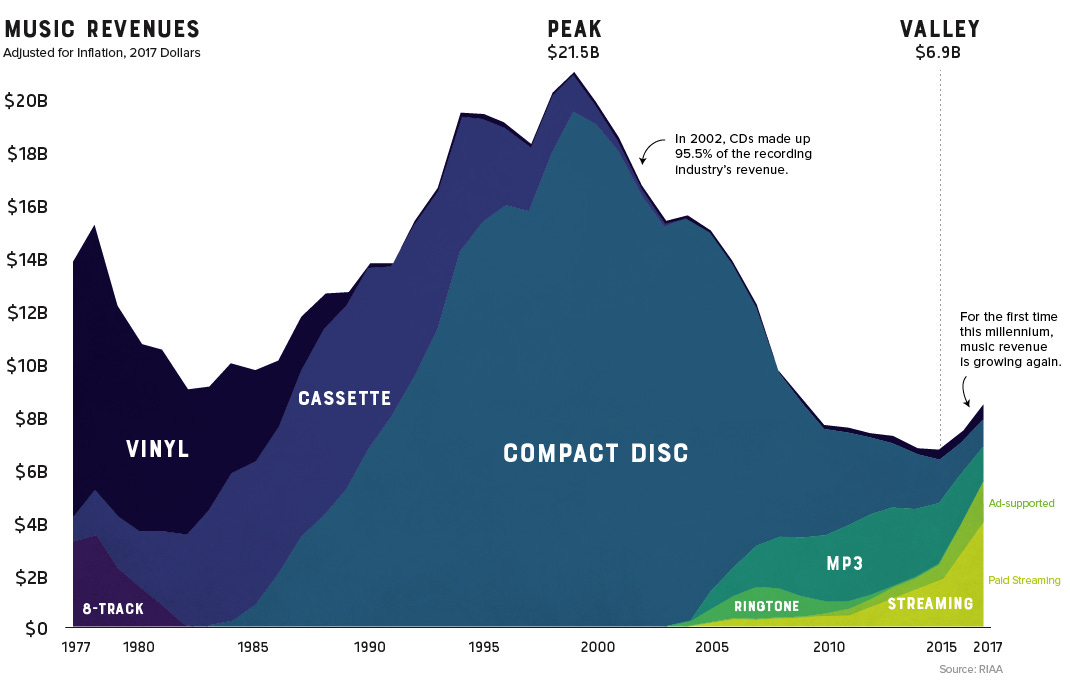

That pattern, by the way—where technology lowers the barriers to entry, creating a flood of new entrants that drives down earnings for all but a very elite group of massive winners—has already happened in publishing and the recording industry, and new waves of it are coming again to those industries, and to film, thanks to AI.

The data is not all bad. Economic rebounds do seem possible. And the long-term result of all that upheaval is that more people are making music and writing novels than ever before. (It’s also worth noting that at the peak of earnings, the recording industry was found to be price fixing. In other words, they were cheating consumers. Actual revenue should never have been that high.)

So, too, with the economy as a whole, where the middle class is shrinking faster than the Colorado river and the world’s richest individuals are worth more than the GDP of most nations. This is why AI is such a seismic shift. As machines can do more and more of the work, how will any of us make money?

It’s not that there isn’t a way. It’s that right now we have no idea.

A recent survey by the Pew Center suggested that a majority of people thought AI would broadly impact the world of work, but a distinct minority thought it would impact THEIR work. Many, many, many of us, it seems, will be echoing our artist friends. “I was told this wouldn’t happen to me!”

She was later given shares of the company, but that was not required under the terms of the engagement.

The situation is more complicated in mixed mediums like comics, where artists and writers will often collaborate on character design and the rest, but that indicates how there is a range and those parts of the process that are more mechanical will be taken over by machine.

When most human artists are just starting, they train their own neural network—the one in their skull—on copies of their favorite artists’ work. If the issue is that the owners of these AI models are charging money for infringing mimicry, that won’t address open source, which is free.